Introduction: the Radical Translations digital resource

The Radical Translations1 project seeks to capture the meaning of radical ideas, language and politics in the revolutionary period by looking at how, when, and why they were translated. The project’s main objectives are to (i) provide a comparative study of the translation and circulation of democratic and free-thinking texts between Italy, France and Britain during the French Revolution and Napoleonic era; (ii) enhance public and academic awareness of the role of translation as an integral element of the revolutionary project; (iii) investigate how translation makes it possible for radical works to be living texts that continually move forward into new communities, new places, new times. This activist intention is often explicitly indicated by translators, such as the anonymous Italian translator of the abbé Grégoire’s address to the citizens of the Alpes-Maritimes, who hoped that his translation could also ‘servire per altri Popoli oppressi, che sospirino la Libertà’ (be of use to other oppressed Peoples who yearn for Liberty) (Grégoire 1793, frontispiece). The Radical Translations project is, thus, both an excavation of little-studied revolutionary-era translations and, more ambitiously, an attempt to mobilise the data collected to illuminate some fundamental changes in translation practices as activist translators, for the first time, used translation to pursue radical political and social goals.

Of course, there is no existing catalogue of revolutionary-era translations, much less a corpus of something called ‘Radical Translations’. Indeed, the role of translation and translators in revolutionary history remains overlooked, despite the ever-growing scholarship addressing the 18th-century boom in translation. The first aim of this project, therefore, was to create a corpus of activist translations that would allow us to investigate why certain texts were selected for translation and what strategies were chosen. A second aim was to highlight the role of translators as mediators of revolutionary culture and practices through reconstructing their social and intellectual identities, networks and itineraries of exile and displacement. At the time of writing, the project has identified:

1682 resources (of which 938 ‘activist’ translations, 607 source-texts and 244 paratext records)

553 translators

499 publishers

236 events

This database is accessible on a public website that includes, amongst other functionalities, five national timelines covering the three linguistic areas of the project (French, English and Italian) enabling users to correlate source texts and translations with macro-events relevant to both the history of radicalism as well as translation. The website also hosts a blog with a running ‘Lives in Translation’ series spotlighting particularly interesting protagonists and texts of the period with a view to enhancing public awareness of the vitality of translation practices in this period.

Activist translations and their paratext

Although small compared to other existing archives (both digital and analogue), the scale of the datasets has enabled a highly granular approach. This is partly due to the unusual focus not on the circulation of revolutionary-era translations per se (something that can be located using existing library catalogues) but on activist translations. What counts as a radical translation and where and how it is found implies an interpretative framework and criteria of selection defined by the research team.2 In addition to the significant intellectual and manual labour of identifying translations and people, a major challenge of this project was to recover the myriad translations and fragments of translation published in newspapers, pamphlets and other ephemeral media, reaching a wider and more diverse readership than book circulation alone. These are often inserted without attribution and not registered in standard library catalogues.

The database thus reflects the richness and variety of 18th-century translation practices by including published translations (whole or partial), retranslations, indirect translations, texts presented as translations, and self-translations. Crucially, we have also decided to include projected, but unrealised or unpublished translations, announced, for instance, in short-lived periodicals or publisher’s prospectuses, as these are important documents that testify to the pace and dynamics of revolutionary culture and language as it was experienced in its own present. To describe this wide range of texts, we adapted the standard Bibliographic Framework Initiative (BIBFRAME) vocabulary as well as creating new classification schemes drawing on terminology from translation studies (e.g. identifying the status of each translation as integral, partial, abridged, etc.).

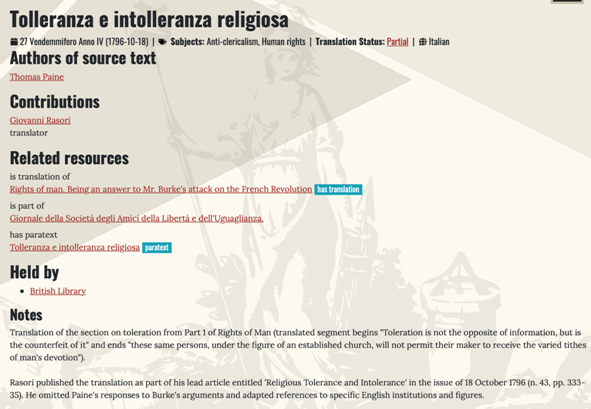

This specialised annotation is evident from the screenshot of the entry on an Italian translation of Thomas Paine (Figure 1) which, in addition to displaying bibliographical information about both source text and translations, also describes radical markers that appear in the text (e.g. the publication date that references the revolutionary calendar), translation status, relevant subject matter, language of the translation, with further contextual information provided in the notes. In fact, Giovanni Rasori’s translation of a section of Paine’s Rights of Man is nested in a longer article from his newspaper Giornale degli amici della Libertà e dell’Uguaglianza, which is itself extremely rich in translations. Following the link, thus, enables users to discover other translations that are part of this journal.

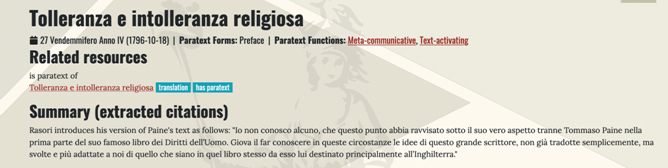

Besides standard bibliographic metadata, we have also described translation paratexts in separate records, which identify their forms (typically titlepages, dedications, epigraphs, prefaces, addenda, notes, etc.) as well as their function. The paratext, or material that accompanies the text proper, is a place where the translator’s voice is often heard and contains precious information about their motivations, the implied or imaginary readers that they address as well as their own interpretations of the relation between the source text and their own historical present. As fascinating and often overlooked documents, the paratexts of translations provide highly self-conscious accounts of how translators negotiated the challenges of cultural transfer, given the frequently asymmetrical power relations between nations, states, regions and languages. As shown in Figure 2, we capture this target-oriented, pragmatic dimension of translation by tagging each record with one or more ‘paratext functions’. Adapted from the work of Batchelor (2018), these four functions describe not so much what a translation is but what it does and how it operates in the target culture. A translation paratext can thus be meta-communicative (when it reflects on the constraints and conditions of translation), hermeneutic (when it presents an in-depth commentary and interpretation of a source text), text-activating (when it makes a case for the relevance of a source text to the present moment) and community-building (when it references groups of imaginary or actual readers).

Radical translators and their networks

If our corpus is constructed in a top-down manner, using an interpretative schema designed by the research team, we have relied on prosopographical data-models to recover the history of translation from the ground up, by reconstructing the networks of publishers, translators and authors. Prosopography can be defined as the investigation of the common characteristics of a group of people whose individual biographies may be untraceable or only indirectly known. It can also be used as an ‘indirect means of research’ to understand: (i) the shape of ideas (philosophical, scientific, political or other) that do not always have an identifiable ‘source’ but nonetheless contribute to the emergence and success of major cultural movements (Enlightenment and humanism are commonly cited examples) and (ii) the activities and motivations of historical actors, especially when it comes to their behaviour and motivation as part of a group (Verboven, Carlier and Dumolyn 2007). As Armando and Belhoste observe (2018, p.15), it is particularly useful for registering the complexity of a ‘pluralist movement’ in which the challenge is to capture both a committed core of known agents and a penumbra of less obvious people who were sporadically involved and/or could be considered adherents in certain contexts.

Therefore, in addition to the bibliographical metadata described above, the Radical Translations project also provides extensive biographical information about translators with the aim of capturing aspects of their social, professional and political identity as members of an informal social group. Here the challenge was to create standardised entries for a diverse set of protagonists. In some cases, the biographies and translation activities are well documented, as in the case of Rasori (Figure 3), for whom we have also included an extended biography, accessible by clicking on the ‘Biography’ tab on the entry itself. In other cases, there are only scraps of information or nothing at all. In fact, out of 553 translators, 271 remain fully anonymous. Given that an important ambition of this project is to de-anonymise some of these translators through further research, we opted to construct simple yet scalable records so that information could be added at a later date. In addition to listing their contribution as translators, authors, publishers or journalists, the biographical records include static attributes (dates, places of birth) as well as acquired or life-attributes: languages spoken, date of death, main place of residence and other important places of residences, the organisations to which they belonged, and the people they knew. We provided links to VIAF and Wikidata, where they existed. Key obstacles here included dealing with multiple spellings of names, the problem of how to attribute pseudonyms (in some cases, several for one person) and register pen-names.

In the case of anonymous translators, our strategy was to include contextual information about cultural and political organisations to which they belonged, including radical circles, printers, publishers, newspapers and other networks of sociability. To do so, we availed ourselves of existing resources such as the CERL Thesaurus, biographical dictionaries, memoirs, published and unpublished correspondence, and other archival sources. Places too are another important point of contact, and our database highlights a number of key cities as important ‘contact zones’ where translators may also have lived and met as exiles, diplomats, refugees or even prisoners, ranging from important centres such as Milan, Paris and London, to border areas that became strategic during the Revolutionary Wars, such as Oneglia, in the Italian region of Liguria, or provincial towns, such as Newcastle and Norwich.

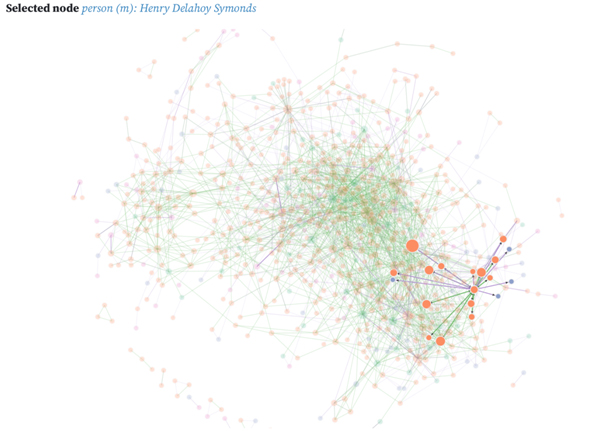

The process of constructing standardised records for a highly diverse group of people, besides being labour-intensive, also raises questions of how prosopography, while differing from network analysis, can overlap with and support it. Together with King’s Digital Lab, we created network visualisations showing the many relations we have mapped in the database (including ‘knows’, ‘translated’, ‘published’, and ‘based in’ relations). On a practical level, social networks are mainly mapped in our database through the relational vector ‘knows’, taken from the FOAF model, which links agents to each other. The ‘knows’ relation is a blunt instrument that does not differentiate degrees of intimacy or specify the nature of a relationship: relations of kinship or marriage are on the same level as professional connections or epistolary correspondence. Moreover, as only agents who are involved in the production of Radical Translations are included in our database, the resulting network is necessarily skewed and does not fully reflect the social world of late 18th- and 19th-century revolutionary movements. Nevertheless, the connections we illuminate define a space where translation creates and supports networks of political solidarity across linguistic and national borders, even in times of war or political repression.

In Figure 4, ‘knows’ and ‘published’ relations are shown simultaneously. Edges link people who knew each other (through information we have extracted from personal correspondence, memoirs and secondary literature) as well as connecting publishers with authors and translators whose works they published. Different colour nodes indicate men (orange), women (green), and anonymous agents are marked violet. The size of nodes is determined by the number of connections they have. The highlighted network is that of the London publisher and bookseller Henry Symonds, an associate of James Ridgway and ‘doyen of the radical press’ (Robinson 2014).3 Symonds is connected to Ridgway, Thomas Paine, William Godwin, Richard Price and other prominent radical figures. His network also includes four anonymous translators whose work he published. Although it does not lead to a full disambiguation, visualising these unidentified figures (who may or may not be the same person) in this way delineates some aspects of their social, professional and political identities and provides circumstantial evidence about their motivations and translation strategies. Seen in this context, they appear… a little less anonymous.

Cultural transfer and chronologies of translation

Finally, the Radical Translations project aims to track not only how translations straddle linguistic and cultural borders but also how they connect two points in time: the moment of production of the source text, and the context in which a translation appears, often in response to the opening and closing of political opportunity. This is especially crucial in the revolutionary period, characterised by a collective sense of time accelerating, as described by Koselleck and others (Koselleck 2004, Hunt 2016, Perovic 2012). To us, translation is where the intercrossing of multiple chronologies becomes visible. To capture this time-sensitive aspect, we have plotted translation activity along five distinct political timelines (France, Ireland, Italy, Britain and the United States). These timelines are highly selective and only contain ‘eventful events’ (see Dunn and Schumacher 2016) relevant for both translation history and the history of radicalism, grouped under nine types.

In the visualisation shown in Figure 5, which is interactive on our website, circles represent events and squares mark the year and place of publication of texts, with gold indicating source texts and blue indicating translations. This composite timeline gives an at-a-glance overview of translation activity in our period, highlighting its rhythm and direction. In this respect, the Italian states are clearly outliers compared to France and Britain, where cultural transfer is sustained throughout the period 1789–1798. In Italy, translation peaks sharply in 1797–1798, during the so-called Republican Triennium, when the French army led by Napoleon occupied large parts of Italy and established several sister republics under French control. As the prevalence of blue squares makes evident, Italian is largely a translating language, with most source texts coming from France. This becomes a two-way exchange in 1797 and 1798, when translations, mostly from the Italian, feature prominently given France’s involvement in the peninsula. Britain, by contrast, provides many inspirational source texts for French and other European revolutionaries in the earlier stages of the Revolution, including some ‘classics’ of Republicanism and the works of the literary celebrity Thomas Paine. The British timeline registers a peak in translation between 1793 and 1795, shortly after Thomas Hardy founded the London Corresponding Society and when public interest in the Revolution had not yet been quashed by the Gagging Acts passed at the end of 1795.4 After this point, translations peter out. In Italy, there is still considerable activity under the Consulate and the Italian Republic until 1803, when the proclamation of the Empire in 1804 puts an end to the national aspirations of the Italian democrats and stricter censorship rules are imposed. The proliferation of translations mirrors what we know about publications in general, namely that there is an explosion of print culture at the onset of the Revolution in both France and Britain, whereas for Italy this happened later, when the French ‘liberated’ Italian cities (De Felice 1962, pp.xii–xix).

We hope other users of the project website will be able to locate specific translations and source texts on these timelines and make their own inferences about how translations may respond to the opening or closing of political opportunity. By affording a type of temporal indexing, these granular chronologies enable users to engage in a ‘narrative-based discovery’, whether by mapping chronologies against each other, discovering new case studies or producing their own methods for reading translation (Jefferies, Filarski and Stäcker 2019, p.169).

More generally, by exploiting digital methodologies, the Radical Translations project provides new ways of exploring the ‘entangled histories’ of revolution in late 18th- and early 19th-century Europe. We have built a flexible, relational database that, while providing reliable metadata on a corpus of little-known material, also makes explicit our research questions and selection criteria and, in so doing, constitutes radical translation practices as a new field of enquiry. In the spirit of histoire croisée, we have exploited the incremental processes of the computational humanities to break with unidirectional models of exchange that posit centres and peripheries, originals and copies, in favour of a multidimensional approach to radical culture that acknowledges its relational and context-dependent nature. Combined with our emphasis on the pragmatics of translation and its function within the target context, this project draws attention to both the ‘resistances, inertias, modifications’ and ‘new combinations’ that emerge in any ‘process of crossing’ (Werner and Zimmerman 2006, p.38). We hope that the user-friendly interface will draw others to browse and search the database, ask their own questions and discover their own entangled histories.

Notes

- Radical Translations: The Transfer of Revolutionary Culture between Britain, France and Italy (1789–1815) is an AHRC-funded project (ref: AH/S007008/1) (2019-2023), based at King’s College London, with the University of Milan-Bicocca as partner institution. Available at: http://radicaltranslations.org/. [^]

- We provide a more detailed account of our selection criteria in the Editorial Handbook on the project’s website: https://radicaltranslations.org/about/database/editorial-handbook/. [^]

- See our database entry for Symonds at https://radicaltranslations.org/database/agents/2184/. [^]

- Williams (1989, p.72) observes that after the events of 10 August 1792 a number of French terms came into use by the London Corresponding Society. [^]

References

Armando D. and Belhoste B. 2018. ‘Mesmerism between the end of the Old Regime and the Revolutions: social dynamics and political issues’. In: Annales historiques de la Révolution française 391:1, 3–26.

Batchelor K. 2018. Translation and Paratexts. London: Routledge.

De Felice R. 1962. I giornali giacobini italiani. Milan: Feltrinelli.

Dunn S. and Schumacher M. 2016. ‘Explaining events to computers: critical quantification, multiplicity and narrative in cultural heritage’. In: Digital Humanities Quarterly 10:3. http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/10/3/000262/000262.html.

Grégoire H. 1793. Indirizzo ai cittadini del dipartimento dell’Alpi Marittime. Anon. (trans.). Nice: Cougnet. https://radicaltranslations.org/database/resources/4720/.

Hunt L. 2016. ‘Revolutionary time and regeneration’, Diciottesimo secolo 1, 62–76. https://doi.org/10.13128/ds-18687.

Jefferies N., Filarski G. and Stäcker T. 2019. ‘Events’. In: Hotson H. and Wallnig T. (eds) Reassembling the Republic of Letters in the Digital Age: Standards, Systems, Scholarship. Göttingen: University Press, 159–70.

Koselleck R. 2004. Futures Past: On The Semantics of Historical Time. Tribe K. (trans.). New York: Columbia University Press.

Perovic S. 2012. The Calendar in Revolutionary France: Perceptions of Time in Literature, Culture, Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Robinson P. 2014. ‘Henry Delahay Symonds and James Ridgway’s conversion from Whig pamphleteers to doyens of the radical press, 1788–1793’. In: The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 1, 61–90.

Verboven K., Carlier M. and Dumolyn J. 2007. ‘A Short manual to the art of prosopography’. In: Keats-Riohan K. S. B. (ed.) Prosopography Approaches and Applications. A Handbook. Oxford: Occasional Publications of the Unit for Prosopographical Research, 35–70.

Werner M. and Zimmerman B. 2006. ‘Beyond comparison: histoire croisée and the challenge of reflexivity’. In: History and Theory 45:1, 30–50. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3590723.

Williams G. 1989. Artisans and Sans-Culottes: Popular Movements in France and Britain During the French Revolution London: Libris, 7–12.